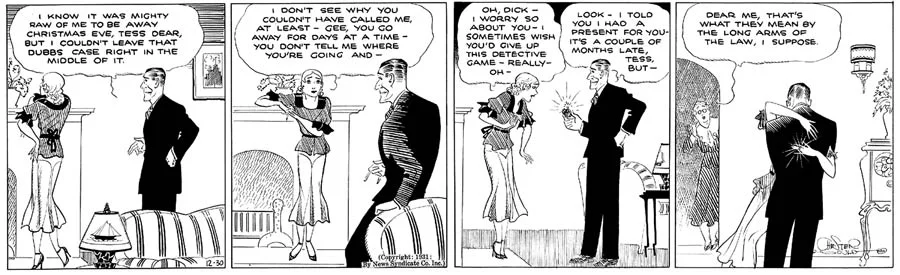

Dick Tracy from the 1930's

When Chester Gould first conceived of his crime-busting hero, his characters and plots were strongly inspired by real-life events and gangsters such as Al Capone [Big Boy] and John Dillinger [Boris Arson]. He also modeled several characters after popular Hollywood stars…Wallace Beery [Steve the Tramp], James Cagney [Jimmy White], Claudette Colbert [Jean Penfield], and Edward G. Robinson [Stooge Viller]. Later, he developed his own brand of unique criminals [Doc Hump, the Purple Cross Gang, the Blank, Jojo Niddle].

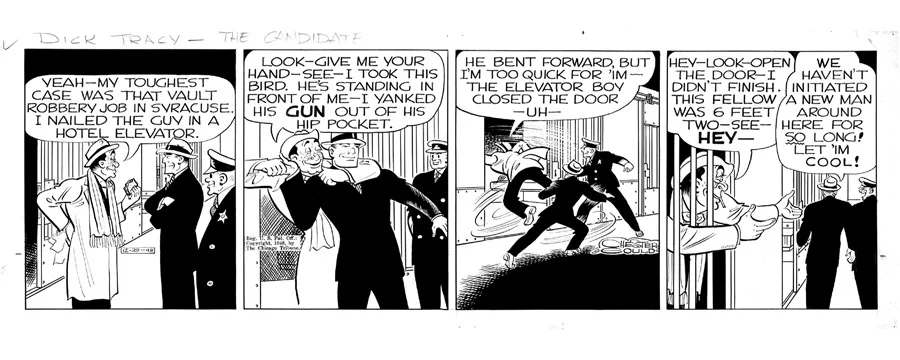

Dick Tracy from the 1940s

In the next decade, Gould’s crooks were so bizarre they were referred to as grotesques, their names reflecting their physical appearance or criminal actions. By the end of World War II, crimes in varied forms of thefts, scams, and extortion prevailed while Gould developed secondary plots involving weddings and births, crime-fighting inventions, and the formation of Crimestoppers.

Dick Tracy from the 1950's

In the third decade, villains and plots became more complex and sophisticated; Gould turned his concerns to organized crime, juvenile delinquency, and domestic crimes. The introduction of Lizz, the policewoman, was a highlight.

Dick Tracy from the 1960's

With the growing interest in the U.S. space program, Gould entered into his controversial “Space Era” which involved the Space Coupe, Air Cars, the use of magnetism, landing on the moon, and international gangsters in outer space.

Dick Tracy from the 1970's

The following gallery is made up of sample strips from the 1970s. Scroll down for letter from Chester Gould to the Newspaper Comics Council on November 2, 1972!

Chester Gould’s Remarks to the Newspaper Comics Council: Nov. 2, 1972

Not too long ago it was fashionable with some newspaper novices to ask: “What’s wrong with the comics?” Well, it’s like this: What was wrong with the comics was the guy who kept asking “What’s wrong with the comics?”

In many cases this was the same individual who put his comics in little “coffins,” 2 ¼ x 7 ¼ inches, and buried them alive on page 43 next to the want-ads—and then had the nerve to ask “What’s wrong with the comics?” I’ve seen as many as 22 on one page!

Suppose his front page, which he so lovingly puts together against all the odds set up by television, were reduced to 2 ¼ x 7 ¼ and run on page 43 next to the want-ads. How much readership do you think it would get? In my opinion, it would get scarcely one one-hundredth the readership a good comic strip gets under the same handicap.

But to start at the beginning, the comic strip was born in the newspaper office. It is the legitimate child of the newspaper and the only feature today that television has not been able to kidnap from newspapers. TV has sports, news, beauty hints, sex, fashions, problems of the heart, and financial news—but the multi-panel comic strip is still the sole property of newspapers. And what do a few editors do about it? They say, “Get that little lowbrow bastard out of my way and lock him in the basement!”

The good newspaper appeals to the masses, not just to any particular stratum. Patterson, McCormick, Hearst and other great newsmen knew and practiced this. And appealing to the masses means understanding the man on the street, not just the PhD’s and/or the oddballs.

It was once pointed out to me that the New York Times carries no comic strips and still is a great newspaper. My answer to that was “Think how much greater it could have been had it carried comic strips. It might have attained a circulation almost as great as the New York Daily News!”

As to the selling of comic strips, I feel there is much to be desired. An important syndicate man recently said to me, “When an editor says ‘I don’t want that strip anymore,’ what can I do?” Well, if the strip is a grabber in the judgment of the salesman, there’s a tool he could use. It’s called salesmanship. Yes, salesmanship. Remember? You present facts, use logic, reason and persuasion. Ford, General Motors, RCA, Zenith, etc., still use it with a great deal of success, wouldn’t you agree?

Salesmanship implies keeping the product sold, also. In the case of comics, it could be used to induce editors to disinter the little comics from their prison cells and to promote them, even to the use of one on the bottom of the front page. Readers’ favorite strips could be used a week at a time on a repeat basis. Any editor who thinks enough of a strip to buy it and give it space—albeit small space—should be willing to back up his judgment.

Now, what does this mean in dollars and cents? Believe me, comics advertising dollars would be a lot easier to comic by if individual newspapers publicized and promoted their comics. Who wants to spend ad dollars with outcasts who, during the week, are locked in tiny cells like drunks?

Let’s face it: You can’t ask the elite with the bucks to spend to join your club if you give the impression you’re ashamed of the membership!

Also, it seems to me that the cozy little group meetings, where everybody engages in repetitive platitudes and listens to critics who lack true understanding of mass newspaper circulation, do not attack the root of the problem. That root is the editor and/or publisher who must be sold on promoting the comics he uses. He must be shown how this will restore prestige to the product and dollars to his advertising till. This is the big job to be done.

I have been drawing and writing Dick Tracy for 41 years. And the Lord willing, I want to go another 41 years. I’m in excellent health and I’m loaded with experience and the joy of doing my job. I consider myself a newsboy. The sole purpose of a comic strip is to sell newspapers: that makes me a newsboy. The American comic strip is responsible for and has sold more newspapers since its creation than any other feature in American journalism, and I’m proud to be part of it.

We have a heritage of the most precious thing ever developed in the good old U.S.A.—the American newspaper and its comic strips. Let’s get out and go with them!

Thank you,

Chester Gould